The Transmediale / CTM joint keynote was Philip Auslander talking on liveness, and there was no way I wasn’t going to be there. He pretty much owns the field of liveness by virtue of writing the book ‘Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture’. It’s a great book that firmly moves performance theory beyond the aura of the body on stage to something that I can reconcile myself with as a media based performer. Having got over the history of mediatisation, the second edition is a lot more contemporary than the first, and CTM was to hear to my understanding his first progression from the position of that second edition.

The standing critique at my research group Interaction, Media and Communication at Queen Mary is that his conclusions smack of technological determinism and largely ignore the audience, and in so doing discount a phenomenological approach (oversimplified as the liveness comes from how the audience receive) and the human-human interaction (oversimplified as the liveness comes from the transition of a group of individuals into a self-identified audience). So it was nice to hear him pretty much flag these criticisms in his opening remarks and change his argument quite significantly. For my research, I needed to absorb his new discourse as a text, and so transcribed my audio recording of it, which I’ve copied below in the full post entry.

As an aside, I found it crazy that somebody whose research is about liveness and is steeped in performance theory could deliver a keynote in such an impenetrable manner. Everybody I asked about it pretty much said they didn’t get anything from it, they didn’t understand a word he said. Or rather, they heard the words, but couldn’t put the sentences together under barrage from the constant delivery. Such dense academic language read verbatim just wasn’t effective communication as a lecture, yet as transcribed I find it near enough perfect for that form. What I’m about to say is clearly psycho-babble, but it felt as it because he wasn’t actually thinking the construction and arguments in his head, that meaning wasn’t somehow imbued in his delivery of the content, and as such the words were just sounds alone.

Photo: Katrina James http://www.flickr.com/photos/transmediale/5415023473/

Update: Transmediale’s live stream of the keynote is now archived: http://www.vimeo.com/20473967

Phillip Auslander - Digital Liveness in a historico-philosophical perspective.

First part is a mildly adapted set of materials adapted from the book. Second part is brand new and written specially for this presentation.

[First part not transcribed: go read the book! The conclusion is largely…]

It is clear from this history that the word live is not used to define intrinsic ontological properties of performance that set it apart from mediatised forms, but is actually a historically contingent term. The default definition of live performance is that it is the kind of performance in which the performers and audience are both physically and temporally co-present to one another. But over time we have come to use the word live to describe performance situations that don’t meet these basic conditions.

[…this is now new…]

The British communications scholar Nick Couldry proposes what he calls two new forms of liveness: online liveness and group liveness. His definitions are:

- online liveness: social co-presence on a variety of scales from very small groups in chatrooms to huge international audiences for breaking news on major websites all made possible by the Internet as an underlying infrastructure.

- group liveness: the “liveness” of a group of friends who are in continuous contact via their mobile phones through calls and texting.

Understood in this way, the experience of liveness is not just limited to specific performer-audience interactions but refers to a sense of always being connected to other people, of continuous technologically mediated co-presence with others known and unknown.

[…and so this is now the new conclusion, before specifically addressing what a ‘digital liveness’ may be]

The emerging definition of liveness may be built primarily around the audience’s affective experience. To the extent that websites and other virtual entities respond to us in real time, they feel live to us. And this may the kind of ‘liveness’ that we now value.

Part Two: Towards a Phenomenology of Digital Liveness

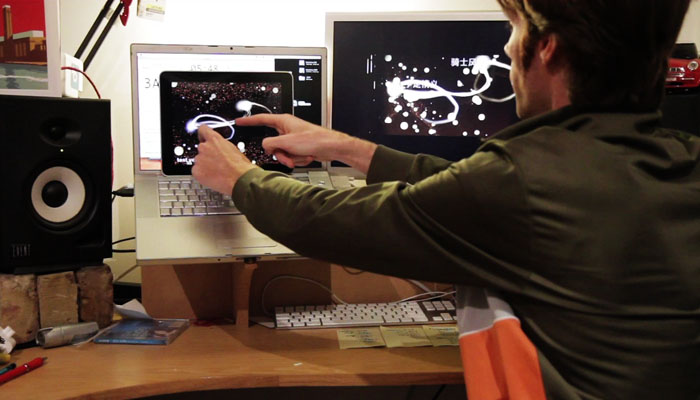

It is this last sentence i wish to revisit. To the extent that websites and other virtual entities respond to us in real time they feel live to us and this may be the kind of liveness we now value. I continue to believe that this statement points to the right direction by nominating the audiences’ experience as the locus of liveness. But I now find that my emphasis on feedback in realtime operations slips into technological determinism by implying that technologies rather than people are the causal agents in the construction of liveness. The need for another way of approaching the question is clear, simply from the fact that while realtime operations and the initiation of a feedback loop may be necessary conditions for the creation of the effect of liveness in our interactions with computers and virtual entities - digital liveness, in short - they are not sufficient conditions. I do not experience all of the realtime operations that my computer performs as live events. For instance the letters appear on my screen as i type but i do not apprehend this phenomenon as live performance by the computer any more than I did when used a typewriter. When I engage in conversation with a chatbot however, I do experience it as a live interaction. This not because what the hardware, software, networks and so on are doing, in the former case are significantly different from what they do in the later case, it’s all ones and zeros after all. Nor does it have simply have to do with the chatbot’s greater anthropomorphism. In keeping with phenomenology’s presence that our experience of the things of the world begins with their disclosing themselves to us, I will suggest that different representations make different claims on us. I am using the word ‘claim’ in the way that the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer uses it in his discussion of aesthetics, and truth and method, a text that will serve as my guide here. I must emphasise however that I am not applying Gadamer’s ideas to the question of digital liveness. For one thing I have no interest in arguing that the interactions I am discussing are necessarily aesthetic in nature, though some of them certainly are. Rather, I aim to construct an argument concerning our engagement with machines and virtual and virtual entities as live that is analogous to Gadamer’s argument that we engage with works of art as contemporaneous rather than an application of it. An analogy rather than application. Gottamer argues that the way a work of art presents itself to it’s audience consitutes a claim, concretiser in a demand that is fulfilled only when the audience accepts it. Broadly speaking I am suggesting that some realtime operations of digital technology make a claim upon us to engage with them as live events and others do not. I repeat that this does not mean that the former is unneccesarily aesthetic in nature. It is crucially important to note that it is up to the audience whether or not to respect the claim and respond to it. In the case of interactive technologies the claim to liveness can be concretised in a variety of demands. Clifford Nass, communications scholar at Stanford University, spearheads a group of researchers who advocate what they call ‘the computer as social actor paradigm’. Doesn’t make a good acronym. Their basic claim is that to interact with our computers in ways that parallel social interactions with other human beings. Clifford Nass and Youngme Moon point to three cues that may encourage social responses to the computer:

1: words for output

2: interactivity, that is responses based on multiple prior input

3: the filling of roles traditionally filled by humans

Nass and his colleagues do not argue that computers are social actors, rather they argue that we behave towards them as if they were. In the terms I’m using here these three cues can be construed as demands in Gottamer’s sense, for example the demand to be perceived as verbal that concretise a claim to liveness. The work of this group also suggests a straightforward reason why we might respond to such a demand: in order to engage in an activity we can interpret as a social interaction or performance, the kinds of activity to which we attach great value. Got tamer argues not only that the work of art makes a claim upon us, but also that in order for a work to be meaningful we must experience it as contemporaneous, a term borrowed from kierkergaard that Gadamer construes as meaning ‘this particular thing that presents itself to us achieves full presence however remote it’s origin may be’. Contemporaneity in this sense is not a characteristic of the work itself, so when Gadamer is speaking of contemporaneity he is not speaking of contemporary art. Contemporaneity is not a characteristic of the work it is a description of how we choose to engage with it. The work of art must be ‘experienced and taken seriously as present and not as something in the distant past’. Got tamer is speaking here of what he calls the temporality of the aesthetic, the way that works of art from a historical context very different from ours may still make claims upon us. I appeal to Gadamer not to frame an argument about digital liveness in relation to historical time rather I am focussing on as aspect of Gottamer’s schema that has to do with bridging a gap between self and other, by rendering the other familiar. A work of art from a past of which we have no direct experience becomes fully present to us when we grasp it as contemporaneous. I suggest that in order to experience interactive technologies as live we similarly must be willing to experience and take seriously their claims to liveness and presence. An entity we know to be technological that makes a claim to be live becomes fully present to us when we grasp it as live. In both cases we must take seriously the claim made by the object for the effect to take place. The crucial point is that the effect of full presence that Gadamer describes does not simply happen, and is not caused by the artwork, or in my analogy the technology. ‘contemporaneity is not a mode of of givenness in consciousness but a task for consciousness and an adjustment that is demanded of it.’ In other words, presence or liveness does not appear in the thing it results from our engagement with the thing and our willingness to bring it into full presence. We do not receive interactive technologies as live because they respond to us in real time as my earlier statement suggested. Rather realtime reaction is a demand that concretises a claim to liveness, a claim that we the audience must accept as binding upon us in order to be fulfilled. Just as artworks from the past do not simply disclose themselves to us as contemporaneous but become us only as a conscious achievement on our part interactive technologies do not disclose themselves to us as live but become so only as a conscious achievement on our part. In Gottamer’s terms an achievement in the case of an artwork ‘consists in holding on to the thing in such a way that it becomes contemporaneous’. The expression ‘holding on’ is important here in the way it suggests both conscious activity and precariousness. It is through a willed act of consciousness that we construe works of art from the past as contemporaneous, or interactive technologies as live, an act that must be actively sustained to maintain the engagement on those terms. Gottamer’s idea that our engagement with works of art takes the form of achievement demanded of consciousness is consistent with this characterisation of the audience position as necessarily active rather than passive. To be part of an audience means to participate rather than simply to be there. His insistence is that it is the audience’s act of consciousness that allows him to experience the work of art as contemporaneous, which I have extended by analogy to the act of consciousness that allows the audience to experience the virtual as live, points the way beyond the technological determinism into which discussions of which these matters, including my own, often fall. Although I am in many ways sympathetic to the computer as social actor paradigm it does not avoid the pitfall of technological determinism. Massey and moon? suggest that mindlessness accounts for our tendency to interact with machines in the ways we interact with human beings despite our knowing that machines are not human. In their account mindlessness is not exactly equivalent to stupidity, rather they define mindlessness as ‘conscious attention to a subset of contextual cues in a situation that results in responding mindlessly, prematurely committing to over simplistic scripts drawn in the past’. Since they offer no account of why we act mindlessly we are thrown back to a technological determinism in which the computer use of words as output for instance causes us to act mindlessly toward it, as if it were a human being. Steve Dixon in his discussion of liveness in the book ‘Digital Performance’ similarly does not steer clear of technological determinism in his suggestion that different modes of presentation, for example live and recorded, trigger different modes of attention from the audience, although he makes a gesture towards the possibility that there is a social dimension to these differences, he concludes by favouring ontological distinctions among media as causing different responses. It is fortuitous that both Nass+moon’s and Dixon’s discussions centre on the matter of audience attention, for Gottamer defines spectatorship in terms of ‘devoting one’s full attention to the matter at hand… The spectator’s own positive accomplishment’. In his account, how we direct our attention is not cued or dictated by the characteristics of the object of our attention as it is for Dixon. Rather it is an accomplishment on our part that is also our part in the interaction through which liveness and co-presence emerges.

To summarise my argument, some technological object - a computer, website, network, a virtual entity - makes a claim on us its audience to be considered as live, a claim that is concretised as a demand in some aspect of the way it presents itself to us: realtime response and interaction or an ongoing connection to others could be examined. In order for liveness to occur the audience must accept the claim as binding upon us to take it seriously and hold on to the object in our consciousness of it in such a way that it becomes live for us. In this analysis liveness is neither a characteristic of the object nor an effect caused by a characteristic of the object, for example it’s medium. Rather liveness is produced through our engagement with the object and our willingness to accept it’s claim. In a footnote to the passage on spectatorship i cited which also has to do with ecstatic experience and loosing oneself by giving oneself over to such experience Gadamer argues against distinctions between ‘the kind of rapture in which it is mans power to produce and the experience of superior power which simply overwhelms us on the grounds that these distinctions of control over oneself and of being overwhelmed are themselves conceived in terms of power and therefore do not do justice to the interpenetration of being outside oneself and being involved in something’. Seen in this light, an encounter of digital liveness that rejects technological determinism in favour of a constructivist argument that technological entities are live only in as much as we see them that way would similarly miss the mark because it would simply shift the balance of power from the technology to the spectator, from technological determinism to spectatorial determinism, so to speak. It is far better to understand that digital liveness derives neither from the intrinsic properties of virtual entities nor simply from the audience’s perceiving them as live. Rather, digital liveness emerges as a specific relation between self and other. The experience of liveness results from our conscious act of grasping virtual entities as live in response to the claims they make on us.