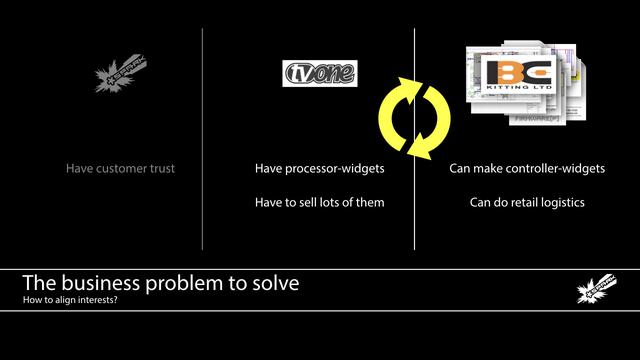

There was a way to align interests and make each party a stage in a chain. Two things made this possible.

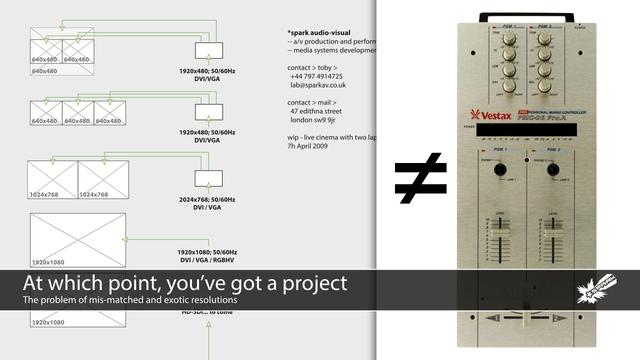

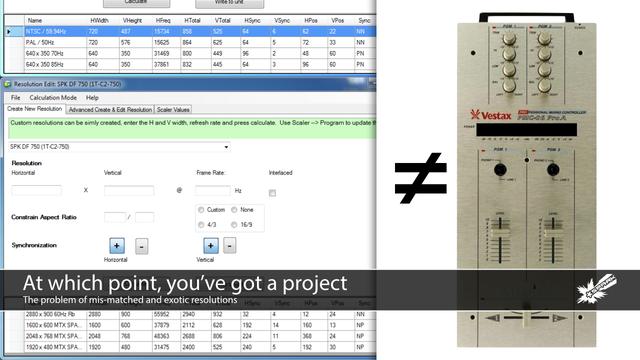

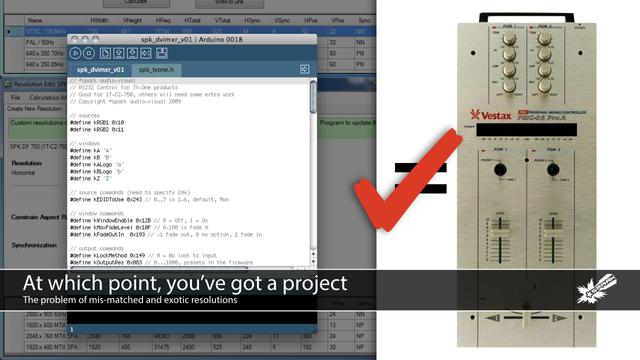

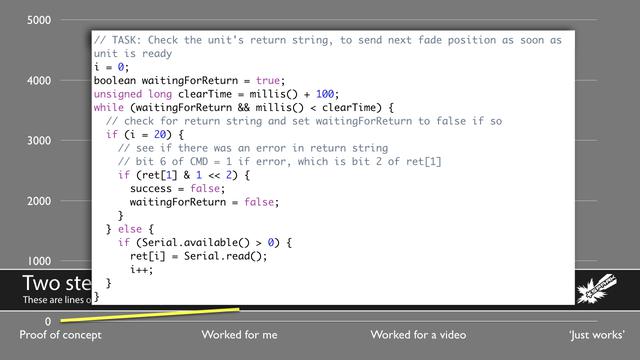

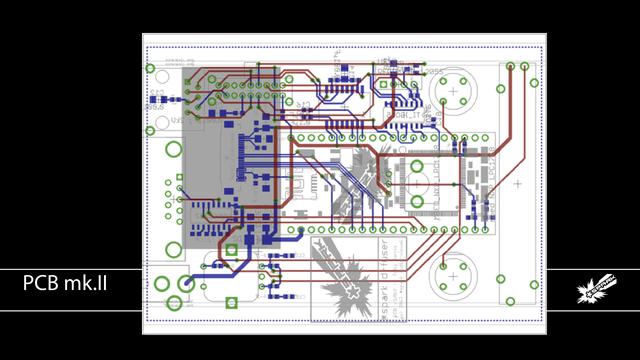

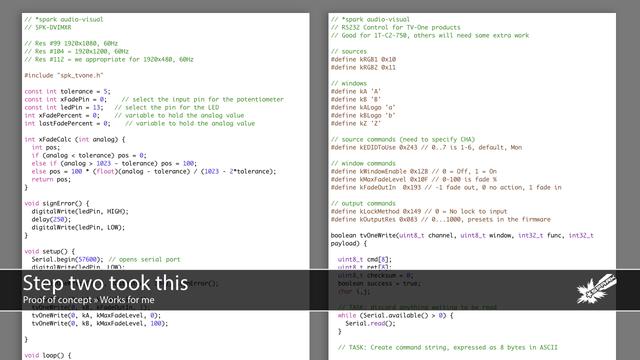

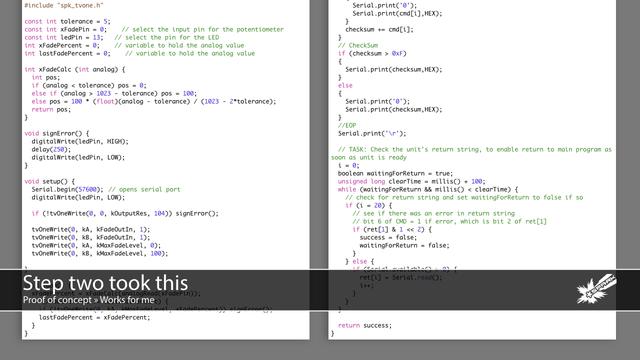

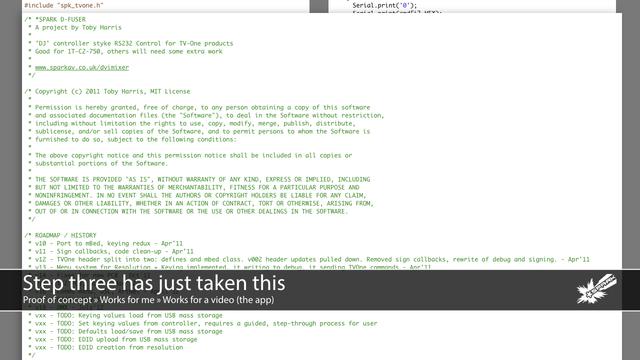

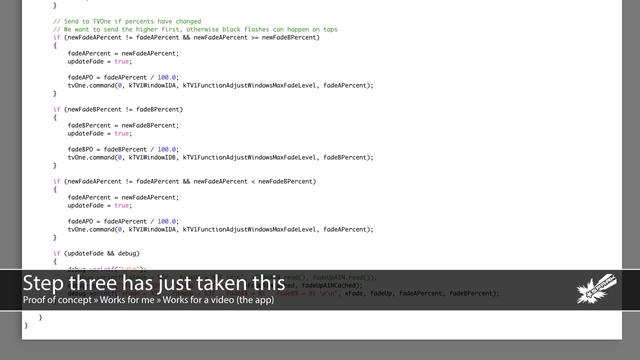

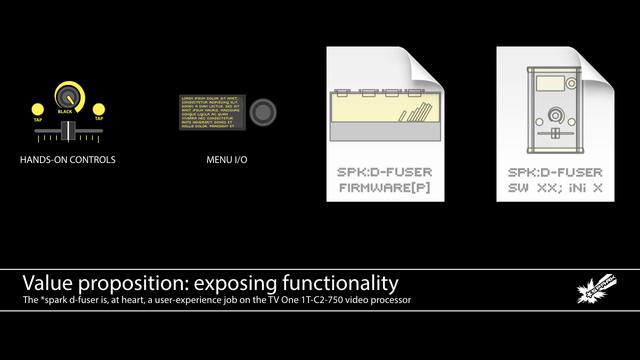

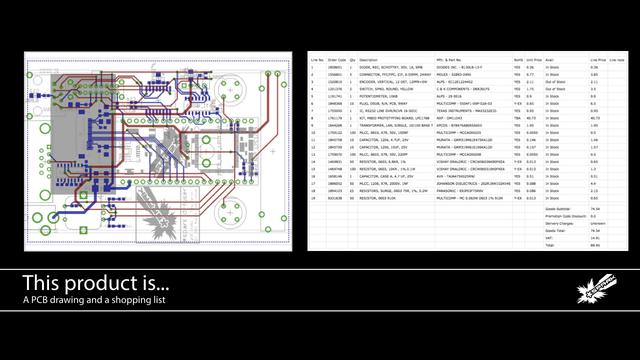

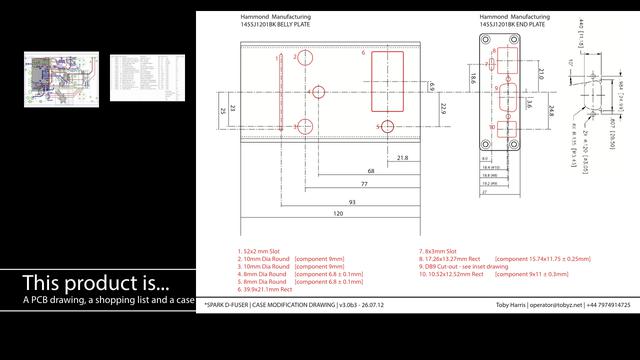

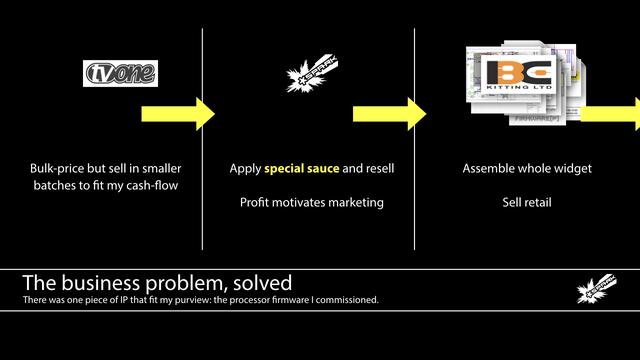

First, there was a piece of IP that was meaningful for production ‘in-house’ – literally, my house.

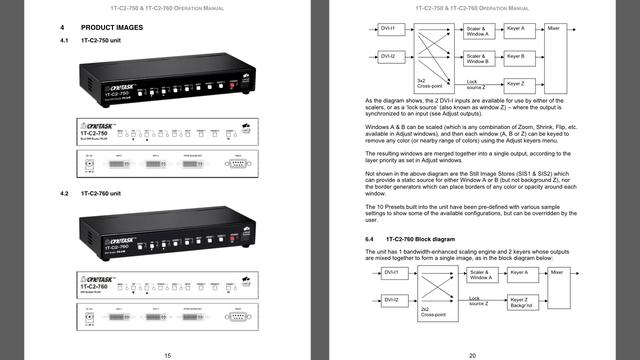

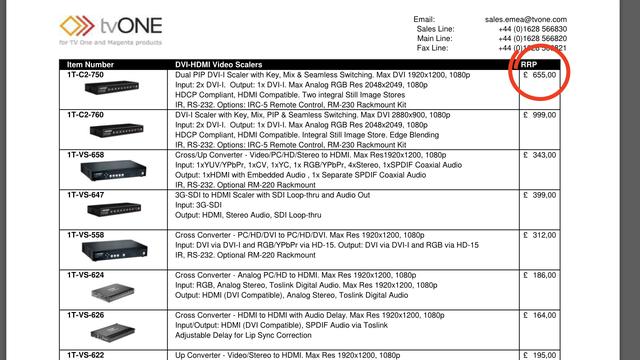

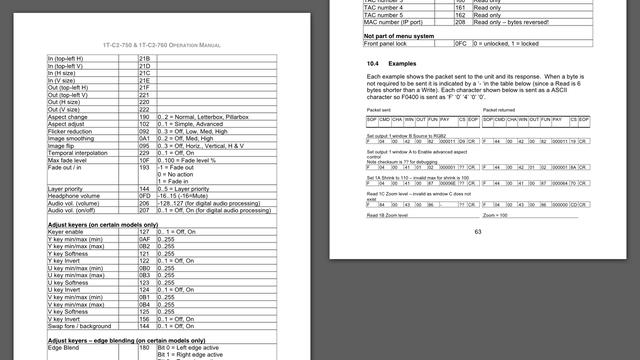

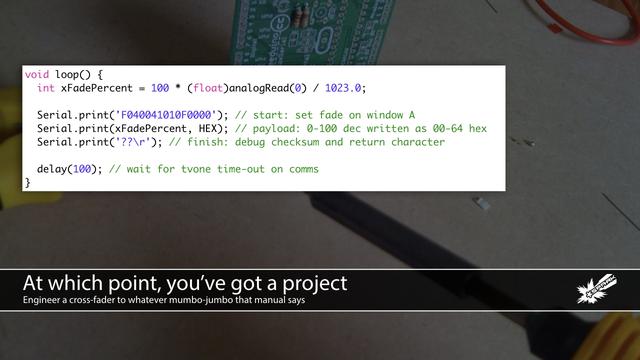

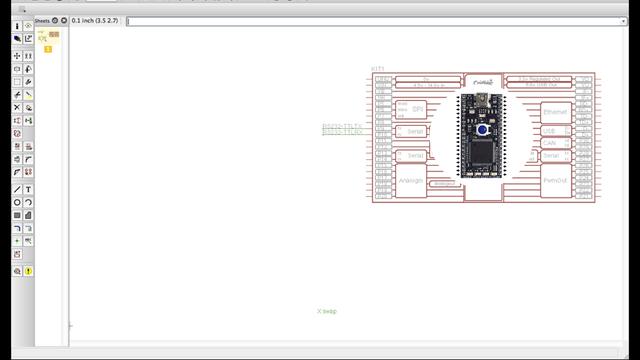

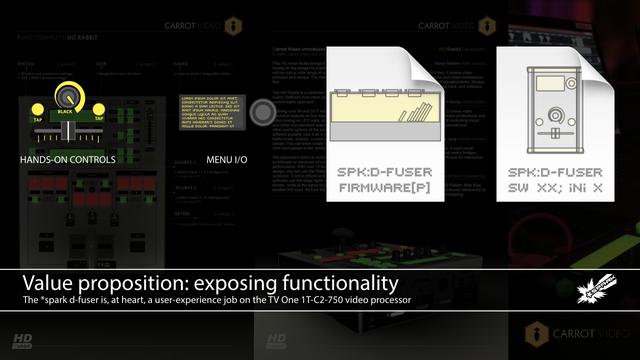

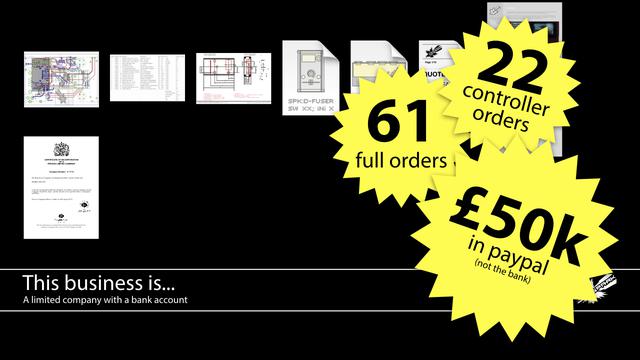

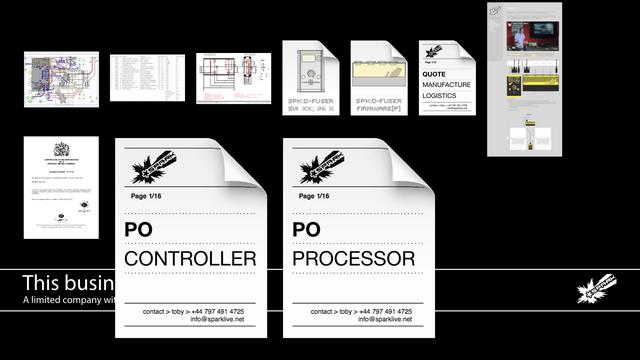

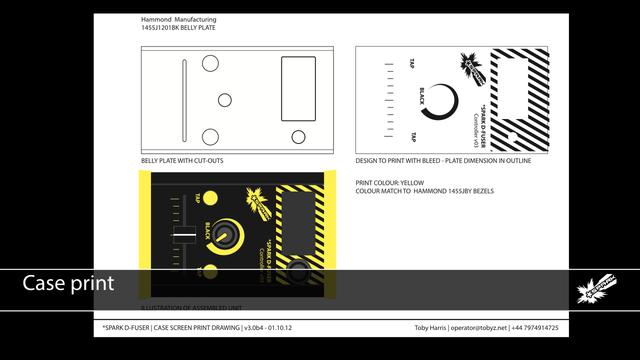

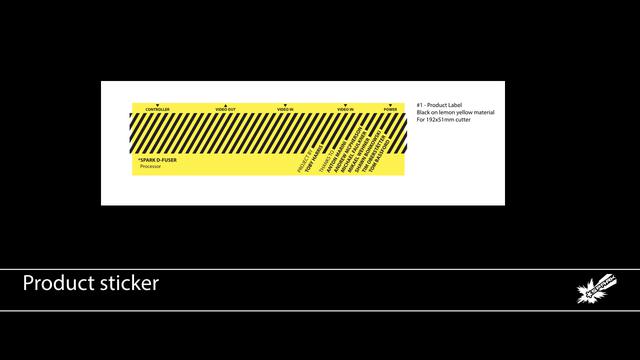

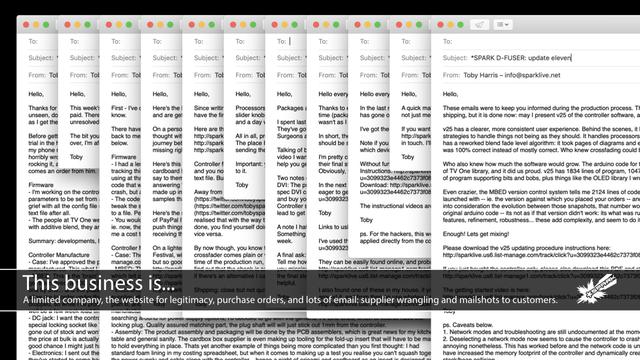

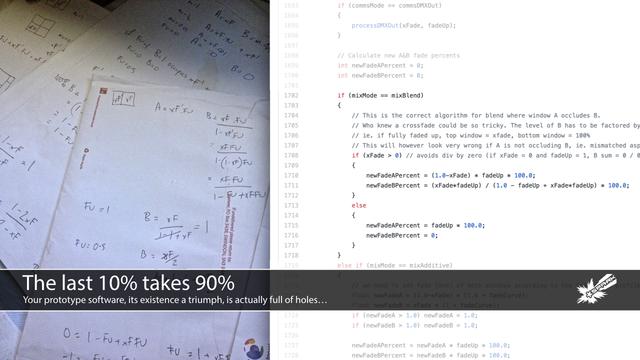

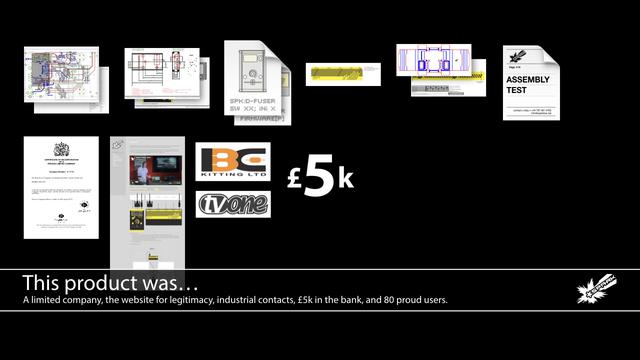

The ability to commission a custom firmware from TV One for the video processor, was my personal reward, and a concrete ‘IP’ advantage over any competitors (e.g. that other video mixer). Or, in this case, my own partners. I could flash this firmware onto the generic TV One processors, stick my nice sticker on, and then resell onto Bob who would pair with the controllers he got made.

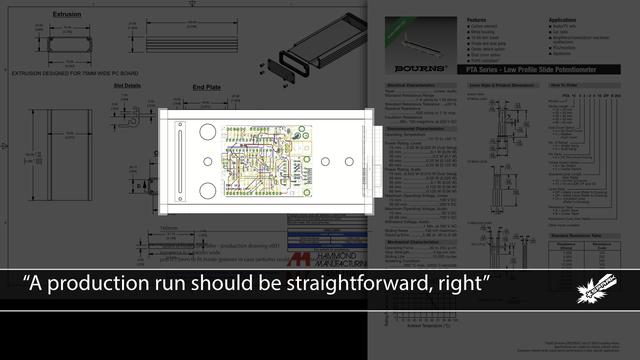

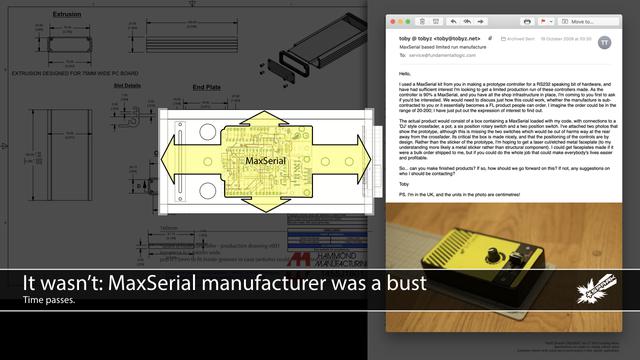

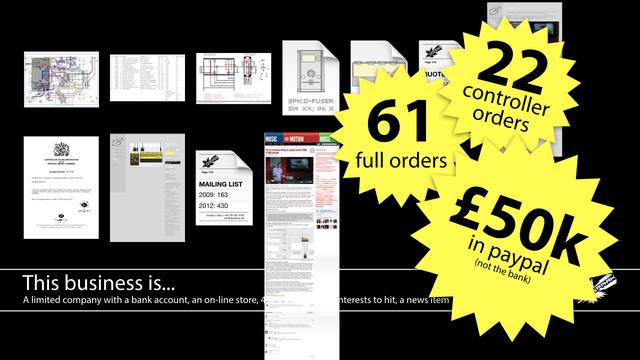

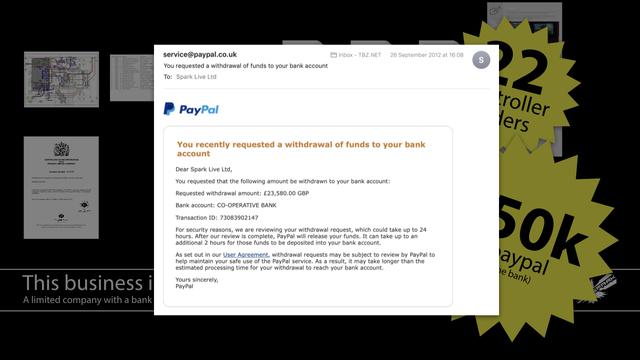

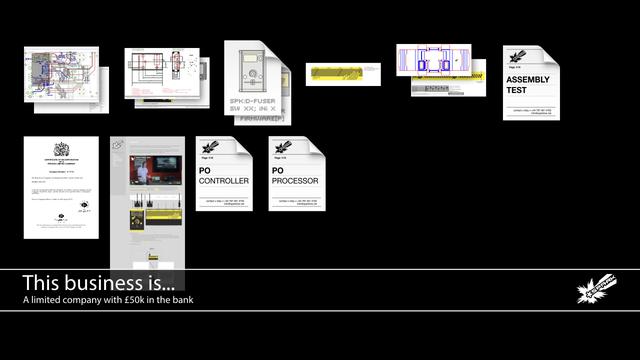

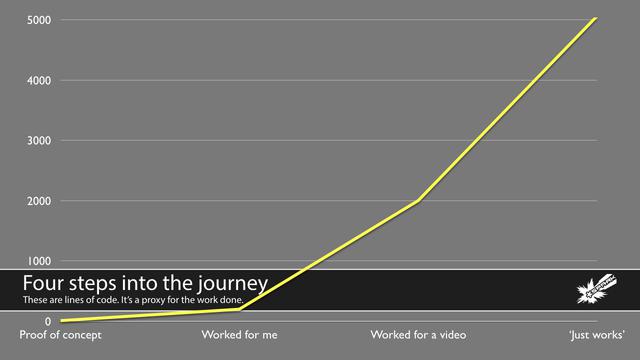

Second, is the call-off order. This would only work if I could get bulk pricing on the processors, but I can’t risk buying 100 up-front. And that would be true even if I had the capital, which I didn’t. Well, companies are people, and people can figure out if there’s a way to make something work for all involved. The answer is a call-off order, in which you split a larger bulk-buy into chunks. Obviously it isn’t quite as good for TV One to deal with e.g. five orders of 20 rather than one of 100, but ultimately if that’s what stands between 100 orders and none, then that’s what to do. I ordered my first chunk with the capital I had, and went back for more when Bob had sold those on. Which is not to say it was frictionless between us, but we both understood each other’s constraints and made it work.

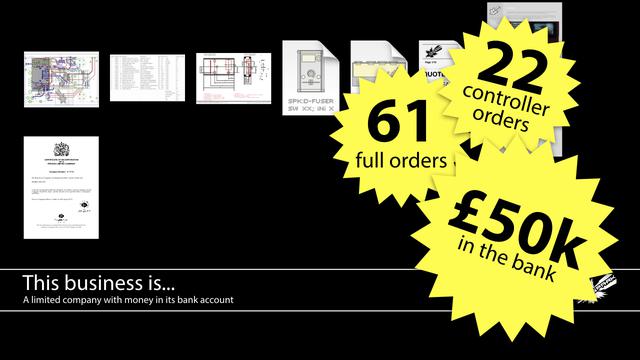

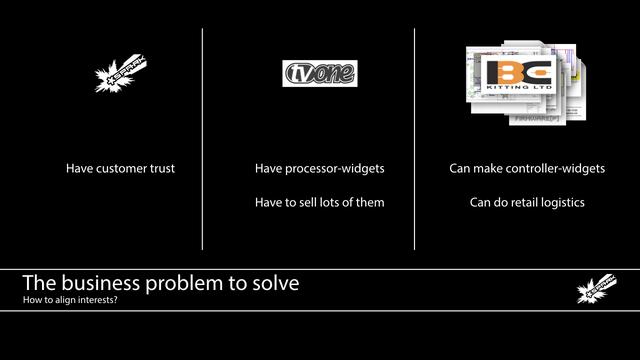

So TV One got to sell lots of processors, I effectively extracted a license fee via wholesaling processors, Bob earnt his cut by making the controllers and doing the retail logistics. All while minimising outlay and risk: controllers were the cheaper part of the package, so the economy gained through making them up-front in bulk was a risk Bob was willing to take. The more expensive part of the package, the processors, were what you wouldn’t want to risk having in stock and unsold or damaged; these could be ordered in smaller quantities nearer on-demand.